In today’s world, nothing is said to be certain, except death, taxes, and that this Wednesday’s meeting is going to be absolutely worthless.

I wouldn’t go as far as comparing meetings with death, but they do bear a striking resemblance to taxes. Often people feel like they’re taxed by their managers to come and spend several hours of their lives pretending to be interested in something.

We have an epidemic of pointless meetings. Executives consider a total of 67% of meetings a failure, which is ironic, because executives are the ones who are most responsible for those meetings, and whether they are failures or not.

There are already a bunch of articles talking about the problem of unnecessary meetings and how to solve it.

More or less, they all give the same advice:

- Include only necessary people in the meeting

- Start with the end goal in mind – ask for an agenda in advance

- Rigid timeline – 30 minutes is 30 minutes

- Every meeting should have a clear purpose

Those are good bits of advice, and they really do work. However, they only work on the symptoms; the actual problem usually lies deeper. In this article, I’d like to address certain problems that are rarely discussed, but with which I’m sure you’ve had some firsthand experience.

Let’s start small, scratching the surface, and then dig deeper, solving the problem of too many meetings in the modern workplace and the faulty logic behind them.

Fake Meetings

This is an old problem, and it‘s been around since the beginning of, well, meetings.

Mike, the manager, sends a meeting invitation to the whole development department, tagging along Ann from marketing and Jenna from Q&A, just in case. The meeting starts, and Mike keeps on explaining to six people in the same room how the company is going to migrate its servers to a new data-center and why it’s absolutely important for everyone to know about it. Meanwhile, Pete, the developer, is secretly working the hotfix for yesterday’s release report on his laptop, nodding approximately every 45 seconds so that Mike could acknowledge that Pete has some neck motoric function left during “the meeting”. Ann draws circles around her temples, and Jenna stabs her lap with a pencil to not fall asleep. The meeting ends, everyone but Mike leaves the room. Mike smiles – his speech was so flawless, not a single question was asked.

This meeting had so many problems – low participation rate, unclear goal, faulty invitation logic. But the very first main problem was to call it a meeting. Call it a monologue, a closet TED talk, anyway – but not a meeting. This was one person sharing information with other people.

Some people think that if you gather more than one person in the same room it’s a meeting. But it’s not, it’s an assembly.

In order to understand if that was a proper meeting or a fake one, ask yourself these questions:

How many people were talking during the meeting?

How many people weren’t talking?

Can I condense this whole meeting into a single Slack message?

Another “fake meeting” type is fake collaboration. While sharing the same space may give an illusion that all people present have a hand in working towards a solution, in reality, they are not. More often than not, other people are simply being informed about solutions that were coined before they even came to the meeting.

Ask yourself these questions:

Did all people participate equally in the problem-solving session?

Was the problem solved before the meeting or after?

Lastly, fake “status meetings”. Those are the meetings when an executive gathers a group of people to discuss the project, while in reality, this executive just wants to see if people are following his commands. There’s nothing bad about status meetings done openly (apart from people spending up to 4 hours per week preparing for status update meetings.), but when organizers pretend that they are something else it undermines team trust and deteriorates team morale at the same time.

Ask yourself these questions:

Is this a status meeting?

If it is, why don’t we just call it that?

Fake Teambuilding

This is especially true for a remote environment – people are far away from each other, and often organizing a meeting is a form of bringing them closer. It is understandable – loneliness and isolation are among things remote workers struggle with the most. If it weren’t for group calls and video meetings, overall communication would be reduced to e-mails and corporate messengers.

But the approach of bloated meetings doesn’t help team building. All it does is make the problem of unnecessary meetings even worse. Useless meetings do not bring people closer. In fact, the opposite happens – tired of them, people feel more sceptical about new meetings and participate less actively in group discussions.

What managers should understand is that there are no team-building meetings.

Successful sessions of group thinking, brainstorming, and problem-solving create a much stronger connection between team members than any superficial “team-building” session.

Only successful meetings build team morale. Again, make sure that those meetings are not “fake collaboration”, but actual collaboration.

Fake Culture

So many companies in recent years have adopted the Agile methodology. And one of the key statements of the Agile manifesto is:

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

I feel like many companies, chasing an Agile mindset, may take this one too far. Yes, it is good to discuss things together, but it’s not good when your only problem-solving approach is to schedule another meeting.

With that approach, the number of meetings quickly gets out of control – some people attend certain meetings and know what’s happening in the company, others – don’t. With so many micro-meetings, someone eventually falls out of the loop, while others think that everything is going absolutely fine, because, well, they “talked”.

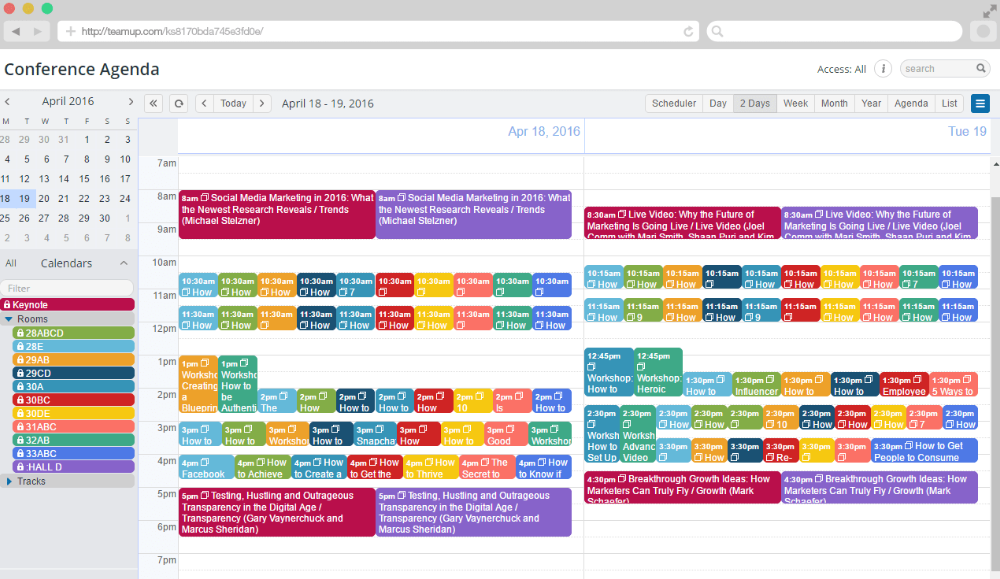

Interactions are good, chaotic interactions are not. Which is why popular methodologies like Scrum and Kanban, even while adhering to Agile manifesto, set very rigid guidelines for meetings: their longevity and frequency.

Daily Standup: 15 minutes, once a day

Sprint planning: 1-2 hours, once in a sprint

Retrospective: 1 hour, once in a sprint

Eventually, companies realize that those rigid timelines are not random. Every interaction, every meeting has a clear goal and a clear timeframe – that’s why those methodologies are so effective and popular nowadays.

Zero Sum Game

Every meeting is a zero-sum game – it either gives your team something or takes something away from them. There are two types of meetings: good meetings and bad meetings. No other types. There are no “neutral” meetings.

The first part of the advice on how to solve the problem of too many meetings has to do with the standard issues: plan your meetings in advance, think why there should be a meeting in the first place (goal), determine who should be in a meeting (active participants) and when there should be a meeting (follow rigid time protocols).

The second part of the advice is to watch for “fake meetings” and fake cultural values – when the problem is deeper than picking up a meeting subject or composing a list of participants. Meetings often give us the illusion of collaboration, problem-solving and direction. If those meetings are planned poorly, they not only fail to achieve the intended result but end up making things worse. So spot fake meetings early, and before you schedule one more, make sure it’s going to be a real one.